NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

- We may need to expand our extraterrestrial search to include binary and multiple star systems.

- Astronomers have long searched for signs of life in single star systems similar to ours.

- The evolution of gas and dust in multiple star systems, according to research published in the journal earlier this month Naturecould serve as a catalyst for life.

Maybe we’re looking for aliens in the wrong places.

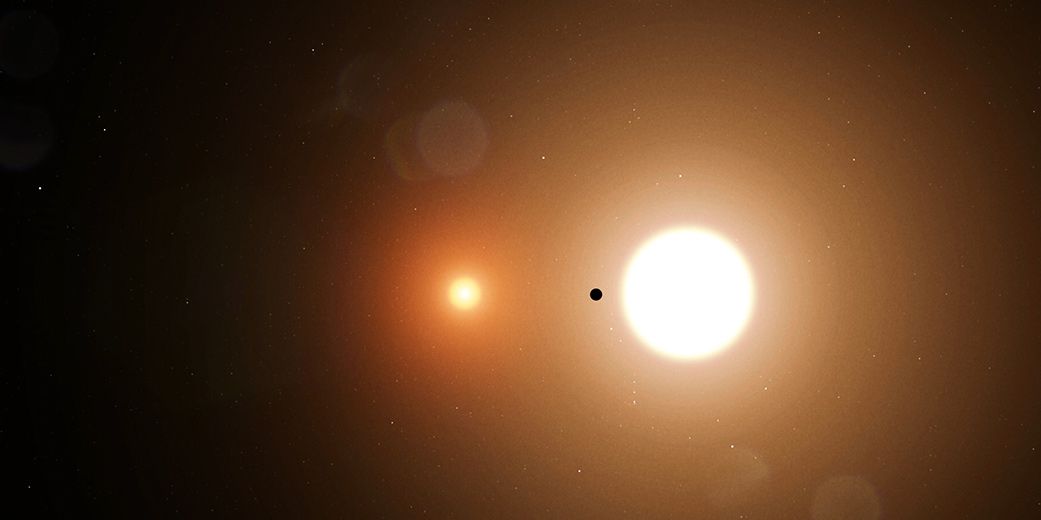

Binary and multiple star systems, which usually consist of two or more stars either orbiting each other or orbiting a fixed point, could hold the key to finding extraterrestrial life, according to a new study by researchers at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

👽 You love science. We also. We’ll help you understand everything – join Pop Mech Pro.

Astronomers have long targeted Sun-like stars and their systems when they scour the universe for the building blocks of life (the organic molecules that form amino acids and other proteins when strung together). After all, it’s the only kind of system we have knows contains life.

However, observations in recent years have shown that half of the star systems containing Sun-sized stars are actually binary systems. These places could just as likely house the ingredients for life, the researchers suggest.

Using the Chilean Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope, the team observed NGC 1333-IRAS2A, a young binary star system 1,000 light-years from Earth. From this data, they developed a series of computer models that mapped the temporal evolution of the system both backwards and forwards. The goal was simple: to study how planets form in binary star systems.

“The observations allow us to zoom in on the stars and study how dust and gas are moving towards the disk,” says Rajika L. Kuruwita, a postdoctoral researcher at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen and one of the authors of the study in a prepared Expression. “The simulations will tell us what physics are at play and how the stars have evolved up to the snapshot we are observing and their future evolution.”

The models showed that the protoplanetary disk — a churning mix of gas and dust surrounding the twin stars — behaved in peculiar ways, speeding up and slowing down at different intervals. The team was able to model the disk’s motion in amazingly granular detail and found that these speed changes occurred roughly every few thousand years, sometimes in as little as ten years.

This happens, the team hypothesizes, because the gaseous, dusty material is periodically sucked in by the massive gravitational pull of the stars. As material raced toward the stars, they warmed up and then brightened. This, in turn, can unleash a cataclysmic jet of energy that rips apart the protoplanetary disk and dramatically alters the evolution of the planets — and their molecular constituents — in the system. Kuruwita and her colleagues published the research results in the journal last month Nature.

“This increases the importance of understanding how planets form around different types of stars,” says Jes Kristian Jørgensen, an astronomer also at the Niels Bohr Institute and one of the leaders of the project, in the statement. “Such results could pinpoint locations that would be particularly interesting to search for the existence of life.”

Next, the team wants to schedule time at other telescopes — including the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope (JWST); the coming Largest-optical-telescope-EVER, the European Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile; and the Square Kilometer Array (SKA) of South Africa and Australia – to observe the star system. These observatories will allow them to see the distant organic molecules (enclosed in both ice and gas form) in even finer detail.

This content is created and maintained by a third party and imported to this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may find more information about this and similar content on piano.io